PERSONALISM

.

by Michael Tsarion

|

|

Wherever there have been powerful societies, governments, religions or public opinions - in short, wherever there was any kind of tyranny, it has hated the lonely philosopher; for philosophy opens up a refuge for man where no tyranny can reach: the cave of inwardness, the labyrinth of the breast - Friedrich Nietzsche

|

In the year 1639, in his book Discourse on the Method, French philosopher Rene Descartes penned the famous line: Cogito, ergo sum or "I think, therefore I am."

It is a line which might have read I doubt, therefore I am, given that Descartes was founding his proof of existence on doubt. His point was that if I'm here to doubt my own existence, I at least confirm that I must really be here to do so. There must be a definite mind executing the task. So far, so good. Existence and consciousness are now proven. Ureka! What a relief.

However, if we dare take another look at the famous line, we might ponder what is really so great about it. Although it transformed philosophy, and instigated what became known as "Cartesian Dualism," what does it actually convey? Not very much. It doesn't tell us what thinking is or what it means to "be." Like so many statements, it leaves out more than it says.

It is a line which might have read I doubt, therefore I am, given that Descartes was founding his proof of existence on doubt. His point was that if I'm here to doubt my own existence, I at least confirm that I must really be here to do so. There must be a definite mind executing the task. So far, so good. Existence and consciousness are now proven. Ureka! What a relief.

However, if we dare take another look at the famous line, we might ponder what is really so great about it. Although it transformed philosophy, and instigated what became known as "Cartesian Dualism," what does it actually convey? Not very much. It doesn't tell us what thinking is or what it means to "be." Like so many statements, it leaves out more than it says.

|

|

Rene Descartes (1596-1650). Although his ideas changed the world, he had, like most philosophers in history, precious little to say about "Being." The human being, as an occupant of the world, is preposterously presented by Descartes as metaphysically schizoid. This bizarre unworkable theory was accepted by major thinkers for centuries, and is still at the heart of materialistic science.

|

|

In fact, it's no easy matter finding answers to what it means to "be." It's far easier to tackle the act of thinking. Martin Heidegger agreed, saying that the whole question of Being fell out of concern thousands of years ago, when thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle decided that Being was really clearer, as a concept, when it is re-defined and equated with "beings" in the ordinary sense.

This conflation allowed them to focus not on Being itself, but on the phenomena available to our senses, namely the objects and entities all around us. This includes human beings. Note the last word - beings. Here we are again.

The ancient Greek word for being is onto, which turns up in the term ontology, denoting the branch of philosophy dedicated to the study of Being.

In English, the problem can be summarized by thinking about the verb "is." When one says that the tree is in the garden, that it is raining, that a friend is coming over, or that this is the truth, what exactly is meant by "is?" What does it allude to? After a little thought, we realize it alludes to existence.

A helpful analogy, when puzzling over Being, concerns the nature of light. Although it illuminates everything we see, it remains unseen and outside normal mental attention. It is very definitely invisible by proximity. This oddity is an essential consideration for anyone investigating the elusiveness of Being.

An easier way of grasping the quarry is to think of any background. Take, for example, the background behind anything seen, the background of everything. All objects and entities sit on something in order to exist and be in relationship with other things. A vase sits on a coaster, which sits on a table standing in the room. Where does the room sit? It's part of a residence standing on the ground, which stands upon the land in a country which is part of a continent standing upon the earth. The earth, in turn, is part of a solar system and galaxy, which are part of the universe.

But on what or in what does the universe, with everything in it sit? Answers on a postcard please?

The key point is that the background is rarely if ever seen or considered. It's not included in everyday sensual apphrehension, even though it is most certainly there. Some kind of nonconscious editing is at work it seems.

Maybe the answer lies in it not being subject to change. All that Being embraces and contains moves and changes, and it is this that makes objects and entities visible to us. Maybe Being doesn't do likewise. Although it allows change and movement, apparently it is beyond these phenomena.

In any case, queried the ontologists, wouldn't it be better if it were noticed? What does science have to say about it? What does philosophy say?

Not much, comes back the answer. For this reason, some tenacious thinkers decided to make the background less elusive. Thinkers such as Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty took up the problem and brought the whole question of Being back into philosophical fashion.

In their minds, if one could articulate facts about the background - about Being - it might help get other problems, mysteries, actions and events into context. Maybe Being is the ultimate "context." Although it is elusive, maybe nothing else can be what it is without it. Maybe it gives shape to what does exist. Being must, therefore, be thought of as highly relevent to beings.

This conflation allowed them to focus not on Being itself, but on the phenomena available to our senses, namely the objects and entities all around us. This includes human beings. Note the last word - beings. Here we are again.

The ancient Greek word for being is onto, which turns up in the term ontology, denoting the branch of philosophy dedicated to the study of Being.

In English, the problem can be summarized by thinking about the verb "is." When one says that the tree is in the garden, that it is raining, that a friend is coming over, or that this is the truth, what exactly is meant by "is?" What does it allude to? After a little thought, we realize it alludes to existence.

A helpful analogy, when puzzling over Being, concerns the nature of light. Although it illuminates everything we see, it remains unseen and outside normal mental attention. It is very definitely invisible by proximity. This oddity is an essential consideration for anyone investigating the elusiveness of Being.

An easier way of grasping the quarry is to think of any background. Take, for example, the background behind anything seen, the background of everything. All objects and entities sit on something in order to exist and be in relationship with other things. A vase sits on a coaster, which sits on a table standing in the room. Where does the room sit? It's part of a residence standing on the ground, which stands upon the land in a country which is part of a continent standing upon the earth. The earth, in turn, is part of a solar system and galaxy, which are part of the universe.

But on what or in what does the universe, with everything in it sit? Answers on a postcard please?

The key point is that the background is rarely if ever seen or considered. It's not included in everyday sensual apphrehension, even though it is most certainly there. Some kind of nonconscious editing is at work it seems.

Maybe the answer lies in it not being subject to change. All that Being embraces and contains moves and changes, and it is this that makes objects and entities visible to us. Maybe Being doesn't do likewise. Although it allows change and movement, apparently it is beyond these phenomena.

In any case, queried the ontologists, wouldn't it be better if it were noticed? What does science have to say about it? What does philosophy say?

Not much, comes back the answer. For this reason, some tenacious thinkers decided to make the background less elusive. Thinkers such as Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty took up the problem and brought the whole question of Being back into philosophical fashion.

In their minds, if one could articulate facts about the background - about Being - it might help get other problems, mysteries, actions and events into context. Maybe Being is the ultimate "context." Although it is elusive, maybe nothing else can be what it is without it. Maybe it gives shape to what does exist. Being must, therefore, be thought of as highly relevent to beings.

|

|

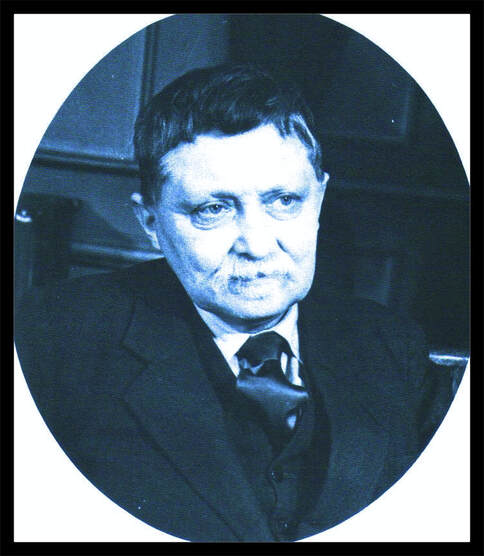

Martin Heidegger (1889-1976). One of the most ridiculed philosophers of all time. Approximately fifty percent of his work has not been translated into English. Most commenters on his philosophy are pathetic specimens. They've failed to explain him in plain English, and there's a very good reason for this scurrilous anomaly. I recommend beginners read Irrational Man, by William Barrett.

|

|

|

|

...it is being that speaks within us,and not we who speak of being - Maurice Merleau-Ponty

|

Heidegger believed that ancient Athenian thinkers, and their descendants, were wrong to abandon Being. It was literally a disaster for the world. He went so far as to condemn Metaphysics and other branches of philosophy for leaving the Question of Being unanswered.

In Being and Time Heidegger concedes that Being isn't an easy subject to discourse upon. This does not mean that it's unimportant. However, a more productive route could be to temporarily direct the inquiry not toward Being itself, but to the kind of person who asks questions about it.

Heidegger believed that every existing thing is in some implicit way indelibly stained, so to speak, by the dye of Being. Everything bears, as it were, the DNA of its origin and shadowy embracer. This is particularly the case with human beings. They are permeated with the fragrance of Being, but have become so accustomed to it that it can be said to no longer exist for them.

Although Being is an elusive phenomenon, the person asking about it is made of flesh and blood, and stands right in front of us. If we direct our inquiry toward his beingness, maybe we can discover something concrete about Being itself.

This is where Heidegger's philosophy is distinctly Existentialist in complexion.

Indeed, the questioner is rendered unique by asking the great question. Animals are incapable of doing so, and most human "beings" always have something else to do.

For this reason Heidegger objected to using terms such as man, human, consciousness, and so on. He preferred to re-name the Questioner of Being, calling him Dasein.

A new philosophical inquiry and approach deserves new nomenclature unencumbered by the verbiage of centuries. In the long run it helps rather than hinders.

Okay, so what do we "know" about Dasein? Well, there's clues in the name. Da-Sein means There-Being or Being-There. This in turn includes the place one finds oneself in, namely the earth or world. Dasein is therefore to be defined as Being-in-the-World.

At last the background is, to an extent, included on equal terms with its occupant. Heidegger chose the odd hyphenated term so we'll always remember that any and all statements about Dasein include statements and truths about his environment. Being, then, is now equated with lived space.

Heidegger proceeds, in Being and Time, to deal with time, as it pertains to human existence, particulalry the existence of he who asks the Question of Being. Maybe we can learn something about Dasein's relationship with time, in our quest to find out more about Being. It seems logical, since time is an intriguing subject, and a mystery to most.

In Being and Time Heidegger concedes that Being isn't an easy subject to discourse upon. This does not mean that it's unimportant. However, a more productive route could be to temporarily direct the inquiry not toward Being itself, but to the kind of person who asks questions about it.

Heidegger believed that every existing thing is in some implicit way indelibly stained, so to speak, by the dye of Being. Everything bears, as it were, the DNA of its origin and shadowy embracer. This is particularly the case with human beings. They are permeated with the fragrance of Being, but have become so accustomed to it that it can be said to no longer exist for them.

Although Being is an elusive phenomenon, the person asking about it is made of flesh and blood, and stands right in front of us. If we direct our inquiry toward his beingness, maybe we can discover something concrete about Being itself.

This is where Heidegger's philosophy is distinctly Existentialist in complexion.

Indeed, the questioner is rendered unique by asking the great question. Animals are incapable of doing so, and most human "beings" always have something else to do.

For this reason Heidegger objected to using terms such as man, human, consciousness, and so on. He preferred to re-name the Questioner of Being, calling him Dasein.

A new philosophical inquiry and approach deserves new nomenclature unencumbered by the verbiage of centuries. In the long run it helps rather than hinders.

Okay, so what do we "know" about Dasein? Well, there's clues in the name. Da-Sein means There-Being or Being-There. This in turn includes the place one finds oneself in, namely the earth or world. Dasein is therefore to be defined as Being-in-the-World.

At last the background is, to an extent, included on equal terms with its occupant. Heidegger chose the odd hyphenated term so we'll always remember that any and all statements about Dasein include statements and truths about his environment. Being, then, is now equated with lived space.

Heidegger proceeds, in Being and Time, to deal with time, as it pertains to human existence, particulalry the existence of he who asks the Question of Being. Maybe we can learn something about Dasein's relationship with time, in our quest to find out more about Being. It seems logical, since time is an intriguing subject, and a mystery to most.

|

|

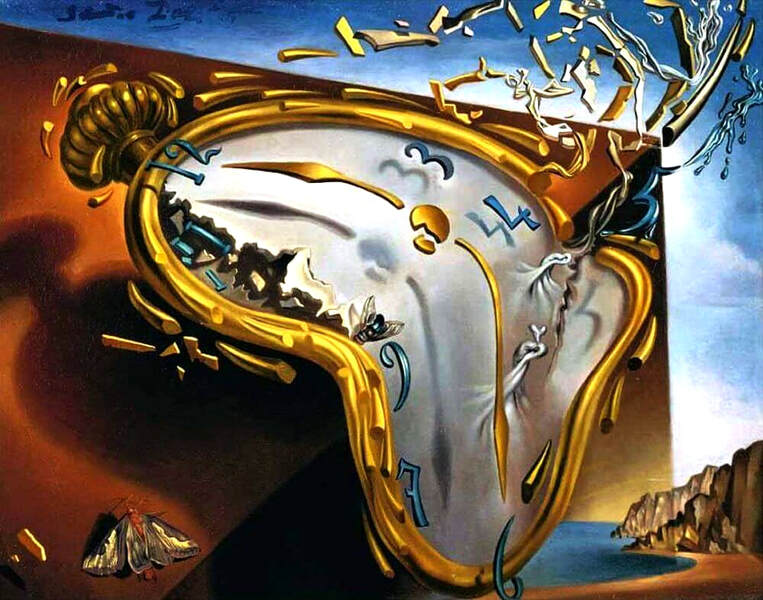

What if our common sense understanding of time is wrong? What if we are time?

|

|

At this point, Heidegger turns his attention to a very important, and wholly obvious fact about human existence - it ends.

Humans die. They die and nothing in the world, no human being and no technique of science changes this fact. No matter what feelings arise, death is the possibility that ends all our possibilities.

So what is it that humans do and become after they digest this disturbing fact? Surely, their entire existence must be rocked and drastically altered by this knowledge of life's brevity.

Descartes' rather empty statement includes the term "think," right enough. But Heidegger, the great anti-Cartesian, asks what kind of thinking are we talking about. Are we talking about thinking radically aware of finitude, or thinking that evades the whole subject?

Well, says Heidegger, let's take a deco. Let's look around at the world and find the answer. Some Existentialist thinkers decided to do just that.

Humans die. They die and nothing in the world, no human being and no technique of science changes this fact. No matter what feelings arise, death is the possibility that ends all our possibilities.

So what is it that humans do and become after they digest this disturbing fact? Surely, their entire existence must be rocked and drastically altered by this knowledge of life's brevity.

Descartes' rather empty statement includes the term "think," right enough. But Heidegger, the great anti-Cartesian, asks what kind of thinking are we talking about. Are we talking about thinking radically aware of finitude, or thinking that evades the whole subject?

Well, says Heidegger, let's take a deco. Let's look around at the world and find the answer. Some Existentialist thinkers decided to do just that.

|

|

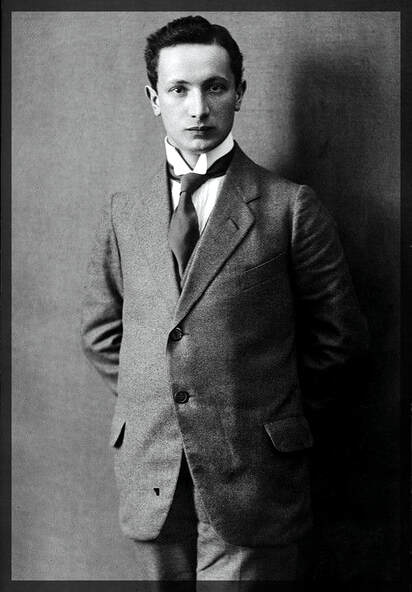

French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961). A leading Phenomenologist, Gestalt psychologist and Existentialist, he applied Heidegger's ontological precepts in exciting and innovative ways. He was particularly interested in perception, as it relates to Being-in-the-World. The act of perceiving objects in the world, and the world itself, inevitably leads one to become conscious of oneself as perceiver. Perception and Selfhood are therefore intimately connected, the former being the guarantor of the latter. As Berkeley said, hundreds of years previously, to be is indeed to be perceived.

|

|

Apparently, beinghood isn't interesting to most people, living, thinking and acting untroubled by the inevitable approach of death.

This type of person Heidegger named Das Man or "The One." He differs from Dasein because he doesn't make death an issue for himself. As a nondescript "hollow man," he gets along just fine in the world of objects and entities. When death comes, he'll have a few regrets, but there's not much he can do about it. The possibility of death hasn't had a special effect on his existence. It's just a medical fact and an inevitability. Sooner or later it happens to everyone, right?

Heidegger referred to this aspect of Existential Time as "temporal finitude." It's the originary kind of time that really gives rise to consciousness. All human beingness or is-ness is based on it, even that of Das Man. That Das Man chooses to live in evasion of temporal finitude, and Being-Toward-Death, on a nonconscious level he's still shaped by it. His enthrallment with domestic and social minutiae is the result of his existential evasion and self-deceptiveness. As such, his entire attitude toward time differs from that of Dasein. His attitude to existence itself - to creativity, nature, meaning and mortality, etc, are unlike that of his more aware counterpart. Heidegger refers to the life and thought of Das Man as inauthentic. It's all based on choices and decisions which can be changed at any time. Indeed, this is what we see happening occasionally if and when a tragedy occurs, when one finally thinks for themselves, rather than as others expect them to.

Authentic Dasein faces the possibility of his death squarely. He realizes that since time is short, he must spend his time wisely and well. He doesn't take it for granted. Moreover, he becomes deeply grateful for his existence. Consquently, if other people don't approve of him, he's not overly concerned or self-condemnatory. Unlike Das Man he is willing to be an "Outsider," and endure the suffering it brings.

This type of person Heidegger named Das Man or "The One." He differs from Dasein because he doesn't make death an issue for himself. As a nondescript "hollow man," he gets along just fine in the world of objects and entities. When death comes, he'll have a few regrets, but there's not much he can do about it. The possibility of death hasn't had a special effect on his existence. It's just a medical fact and an inevitability. Sooner or later it happens to everyone, right?

Heidegger referred to this aspect of Existential Time as "temporal finitude." It's the originary kind of time that really gives rise to consciousness. All human beingness or is-ness is based on it, even that of Das Man. That Das Man chooses to live in evasion of temporal finitude, and Being-Toward-Death, on a nonconscious level he's still shaped by it. His enthrallment with domestic and social minutiae is the result of his existential evasion and self-deceptiveness. As such, his entire attitude toward time differs from that of Dasein. His attitude to existence itself - to creativity, nature, meaning and mortality, etc, are unlike that of his more aware counterpart. Heidegger refers to the life and thought of Das Man as inauthentic. It's all based on choices and decisions which can be changed at any time. Indeed, this is what we see happening occasionally if and when a tragedy occurs, when one finally thinks for themselves, rather than as others expect them to.

Authentic Dasein faces the possibility of his death squarely. He realizes that since time is short, he must spend his time wisely and well. He doesn't take it for granted. Moreover, he becomes deeply grateful for his existence. Consquently, if other people don't approve of him, he's not overly concerned or self-condemnatory. Unlike Das Man he is willing to be an "Outsider," and endure the suffering it brings.

|

|

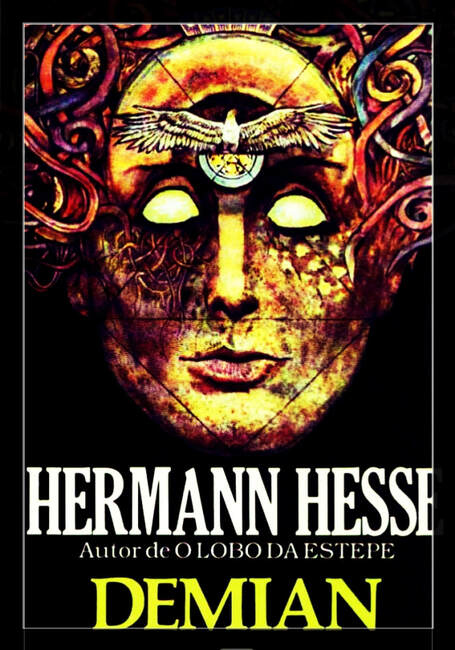

Many of the greatest modern novelists were influenced by Existentialism. This is particularly the case with Herman Hesse. His books Demian and Steppenwolf have been read by millions. Other notable works with Existentialist themes are Nausea, by John-Paul Sartre, The Stranger, by Albert Camus, The Outsider and Beyond the Outsider, by Colin Wilson. Books of this caliber have in turn influenced Existentialist movies such as The Moon and Sixpence, The Razor's Edge, Paris Texas, The Graduate, Wings of Desire, Kes, Fearless, About Schmidt, One-Hour Photo, Being There, Vanilla Sky, The Truman Show, American Beauty and Sex, Lies and Videotape, etc.

|

|

We see from this brief sketch, how much more has been added to Descartes' short, rather empty phrase.

Heidegger's thought also impacted that of dozens of other philosophers throughout time. He not only contradicted his own teacher Edmund Husserl, but everyone you care to think of. It decimated the dualism of Descartes, the Idealism of Kant and Hegel, the metaphysics of Plato and Aristotle, the scholasticism of many a Christian of the monastic tradition, and the baloney of the Positivists and Pluralists. He also excoriated Rationalism, and the inhuman doctrines, paradigms and practices of science and technology.

Although Heidegger did not identify himself as an Existentialist, per se, there can be no doubt that his thought heavily impacts this branch of philosophy. Indeed, Heidegger was influenced by both Kierkegaard and Nietszsche. His ideas were central to the formation of Existential Psychology.

His reluctance about the appellation stemmed from his antipathy to the thought of French Existentialists who generally misunderstood his work, and wrongly applied his teachings; men such as Jean-Paul Satre and Albert Camus. Heidegger's body of work was more favorably understood and applied by Frenchmen Gabriel Marcel and Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

Heidegger's thought also impacted that of dozens of other philosophers throughout time. He not only contradicted his own teacher Edmund Husserl, but everyone you care to think of. It decimated the dualism of Descartes, the Idealism of Kant and Hegel, the metaphysics of Plato and Aristotle, the scholasticism of many a Christian of the monastic tradition, and the baloney of the Positivists and Pluralists. He also excoriated Rationalism, and the inhuman doctrines, paradigms and practices of science and technology.

Although Heidegger did not identify himself as an Existentialist, per se, there can be no doubt that his thought heavily impacts this branch of philosophy. Indeed, Heidegger was influenced by both Kierkegaard and Nietszsche. His ideas were central to the formation of Existential Psychology.

His reluctance about the appellation stemmed from his antipathy to the thought of French Existentialists who generally misunderstood his work, and wrongly applied his teachings; men such as Jean-Paul Satre and Albert Camus. Heidegger's body of work was more favorably understood and applied by Frenchmen Gabriel Marcel and Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

|

|

French Existentialist Gabriel Marcel (1889-1973). He was the foremost exponent of the philosophy of Personalism. He was influenced primarily by Soren Kierkegaard and Martin Heidegger.

|

|

Heidegger's ideas on nature, art, poetry, language, technology and religion, etc, are chiefly derived from to earlier thinkers of the first rank, Friedrich Holderlin and Rainer Maria Rilke.

|

|

Heidegger's extraordinary philosophy serves as a superlative exegesis on the profound poetry of Friedrich Holderlin (1770-1843), Germany's greatest national poet, and Czech poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926).

|

|

Heidegger was fascinated with words and had his own poetic style of writing and speaking. Corridors in the university were jam-packed with students and teachers eager to hear him speak. They had never heard German spoken that way before, nor thought about how extraordinarily fluid their interaction with the world actually was.

Why hadn't any of them noticed the handle of the door as they turned it? Why hadn't they said "hello" to the blossoming tree in the courtyard? Why hadn't they noticed the light around them, or caressed the paper on which they wrote? How much of what exists remains in the dark? We say we are "conscious" beings, but are we? Is it true, or simply a case of self-deceptiveness? Surely, most of what we miss is missed because of its very proximity. So it is with Being itself. It doesn't strike out at us, parade, or beckon to be noticed. It's the background, yes, but it doesn't care if it's ignored.

One of Heidegger's key subjects was Gratitude. He reminded his students and listeners that in German there is a conspicuous etymological similarity between the word for thinking - Denken, and word for gratitude - Danken.

It's not an accident, said Heidegger.

There are certain ways or comportments required for coming into contact with Being, and one of them is thankfulness. When each and every thought is a genuine act of gratitude for existence, we're on our way toward authenticity in the highest sense of the word. No other being can get there without sincerely adopting this comportment. It's just not possible.

It follows that the world we inhabit is largely populated by "inauthentic" types. It is they who build our cities and provide us with endless distractions and entertainments. It is they who provide us with a hundred brands of Vodka and chewing gum. It is they who teach our children and make our laws. It is they who devalue the natural world (Umwelt) in favor of the social world (Mitwelt). It is they who coerce us to value what we own rather than what we think and are. It is they who lose if and when we really do confront our temporal finitude, and live meaningfully for a change.

Why hadn't any of them noticed the handle of the door as they turned it? Why hadn't they said "hello" to the blossoming tree in the courtyard? Why hadn't they noticed the light around them, or caressed the paper on which they wrote? How much of what exists remains in the dark? We say we are "conscious" beings, but are we? Is it true, or simply a case of self-deceptiveness? Surely, most of what we miss is missed because of its very proximity. So it is with Being itself. It doesn't strike out at us, parade, or beckon to be noticed. It's the background, yes, but it doesn't care if it's ignored.

One of Heidegger's key subjects was Gratitude. He reminded his students and listeners that in German there is a conspicuous etymological similarity between the word for thinking - Denken, and word for gratitude - Danken.

It's not an accident, said Heidegger.

There are certain ways or comportments required for coming into contact with Being, and one of them is thankfulness. When each and every thought is a genuine act of gratitude for existence, we're on our way toward authenticity in the highest sense of the word. No other being can get there without sincerely adopting this comportment. It's just not possible.

It follows that the world we inhabit is largely populated by "inauthentic" types. It is they who build our cities and provide us with endless distractions and entertainments. It is they who provide us with a hundred brands of Vodka and chewing gum. It is they who teach our children and make our laws. It is they who devalue the natural world (Umwelt) in favor of the social world (Mitwelt). It is they who coerce us to value what we own rather than what we think and are. It is they who lose if and when we really do confront our temporal finitude, and live meaningfully for a change.

|

|

As Emile Durkheim said: society is little more than a dust of individuals.

|

|

It is they - the inauthentic masses and their puppeteers - who benefit from Das Man's failure to confront his temporal finitude and the existential anxiety it elicits.

Heidegger's critiques of religion follows a similar line as those against technology. The religious man flees the anxiety aroused within him over life's inevitable termination. He invents a god and an afterlife to appease it.

The man of science confines his attention to the "improvement" of the world he occupies, as if it makes good use of his limited time. But is he not violating time itself? He may be a busy man, and as active as hell, but what about quality? Frenetically attending to a million projects has little bearing on what really matters. Look around and notice the everyday situation, advises Heidegger. Why all the manic gossip and chit-chat? Is it real communication? Are we really progressing amid all the theories of science? Do we ever contemplate what is being lost?

Although Heidegger was a critic of metaphysics and other branches of philosophy, he was certainly a Personalist.

Like Berkeley, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Stirner, Marcel and a few others, Heidegger's ideas on the relevance of Being lead us to a state of "dwelling," in which whatever experiences occur to us are ours and ours alone. There's nothing collectivized about it. Most commenters on his work are very reluctant to even broach this aspect.

Personalism does not call for solipsistic retreat. It does not mean that one hasten either to monasteries or mountain caves. It's not about leaving the human race behind. Rather, it's about being truly human, truly oneself.

Heidegger's critiques of religion follows a similar line as those against technology. The religious man flees the anxiety aroused within him over life's inevitable termination. He invents a god and an afterlife to appease it.

The man of science confines his attention to the "improvement" of the world he occupies, as if it makes good use of his limited time. But is he not violating time itself? He may be a busy man, and as active as hell, but what about quality? Frenetically attending to a million projects has little bearing on what really matters. Look around and notice the everyday situation, advises Heidegger. Why all the manic gossip and chit-chat? Is it real communication? Are we really progressing amid all the theories of science? Do we ever contemplate what is being lost?

Although Heidegger was a critic of metaphysics and other branches of philosophy, he was certainly a Personalist.

Like Berkeley, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Stirner, Marcel and a few others, Heidegger's ideas on the relevance of Being lead us to a state of "dwelling," in which whatever experiences occur to us are ours and ours alone. There's nothing collectivized about it. Most commenters on his work are very reluctant to even broach this aspect.

Personalism does not call for solipsistic retreat. It does not mean that one hasten either to monasteries or mountain caves. It's not about leaving the human race behind. Rather, it's about being truly human, truly oneself.

|

|

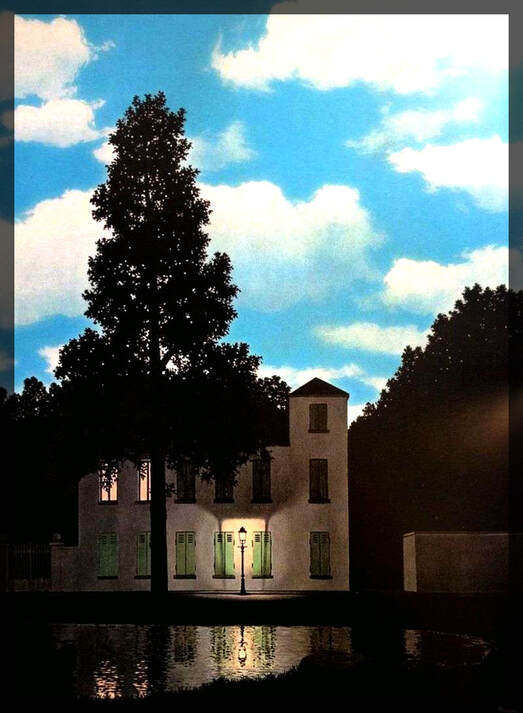

All things meet on the background, but never speak of it.

|

|

|

|

If you cannot be with yourself, who can you really be with? - Mtsar

|

Remember the old Hermetic adage? He who knows does not speak, whereas he who speaks does not know.

What does it really mean?

It's a precept that turns up in ancient Buddhist, Zen and Taoist texts, but can be understood with simple common sense.

If I have a profound thought or experience, it is not enhanced if ten thousand people hear about it. It's the most common thing in the world for Das Man to blab all about his dreams, thoughts, emotions, beliefs and ideas, and impress people with his or her "philosophy" of life. It's so customary and familiar that we never stop to think if it constitutes a crime against the Self.

But a contemplative person asks whether the world as we experience it has been improved by such a practice? For all of it, do we have wisdom or noise?

What might happen if I simply keep it to myself? It's what the term Hermetic actually means? It refers to Hermes, the keeper of secrets, and to the Hermetic Tradition, in which initiates preserve with utter gratefulness insights received about the Great Mystery.

Or course, this has little to do with Das Man. He's not only in the Crowd, the Crowd is very definitey in his head. His perpetual chit-chat is necessary to him. It's one of the chief means by which he avoids what Heidegger calls Sprache or "Speech."

It's all based on the truism that no matter what experience I have, of a profound nature, it simply cannot be shared. Personalism is, therefore, based on the assumption and rule that it should not be shared.

The object inspiring you is trying to open a dialogue with you, and you alone. Too bad you're impervious to its call.

This is not to say that normal communication on domestic and intellectual matters terminates. Certainly, one must still discourse about philosophical matters in a general way. Personalism is defined by not sharing what one believes in their heart. We all distrust the person who cannot keep a "secret." What about ourselves? Can't we tell when something is a secret or not, something to remain undisclosed? I guess not.

With this in mind, I've written works to clarify my philosophy of Objectionism. As I explain in Disciples of the Mysterium, I object to the fact that the world is full of ideas which should have remained undisclosed. The world would have been a far better place, and far more enriched, if the term Hermetic was understood and honored.

We're flooded with sacred texts and scriptures, sects, cults, yogic systems, gurus, pundits, hymns, prayers, mantras, speeches, doctrines, drums, bells and tamborines. No bloody silence.

Wisdom of the heart remains intact as long as it is kept within the heart, not sold cheap on the street corner.

We've defaced truth by way of our leaky brains and idle tongues. We've filled the planet with our cacophony. We've placed high-powered explosives in front of Aladdin's Cave, blasted it open to the winds, and ransacked the place. Instead of the heavy silence of the sanctum, we prefer the crowded market-place full of howls, shrieks, cavorting and intoxication. As Heidegger says, Being, the darkest of all terms, has abandoned us. Our very call to it turns it away forever. No wonder!

After all, what do we learn from I think, therefore I am? Why could Descartes not have kept it to himself? It's really about his beinghood anyway. Why were the words Know Thyself, written at the oracle of Delphi? Has it done anyone any good? Why couldn't people work it out for themselves? Because, obviously, that's the hard part. Writing or saying it is damned easy. Hence the appeal.

What does it really mean?

It's a precept that turns up in ancient Buddhist, Zen and Taoist texts, but can be understood with simple common sense.

If I have a profound thought or experience, it is not enhanced if ten thousand people hear about it. It's the most common thing in the world for Das Man to blab all about his dreams, thoughts, emotions, beliefs and ideas, and impress people with his or her "philosophy" of life. It's so customary and familiar that we never stop to think if it constitutes a crime against the Self.

But a contemplative person asks whether the world as we experience it has been improved by such a practice? For all of it, do we have wisdom or noise?

What might happen if I simply keep it to myself? It's what the term Hermetic actually means? It refers to Hermes, the keeper of secrets, and to the Hermetic Tradition, in which initiates preserve with utter gratefulness insights received about the Great Mystery.

Or course, this has little to do with Das Man. He's not only in the Crowd, the Crowd is very definitey in his head. His perpetual chit-chat is necessary to him. It's one of the chief means by which he avoids what Heidegger calls Sprache or "Speech."

It's all based on the truism that no matter what experience I have, of a profound nature, it simply cannot be shared. Personalism is, therefore, based on the assumption and rule that it should not be shared.

The object inspiring you is trying to open a dialogue with you, and you alone. Too bad you're impervious to its call.

This is not to say that normal communication on domestic and intellectual matters terminates. Certainly, one must still discourse about philosophical matters in a general way. Personalism is defined by not sharing what one believes in their heart. We all distrust the person who cannot keep a "secret." What about ourselves? Can't we tell when something is a secret or not, something to remain undisclosed? I guess not.

With this in mind, I've written works to clarify my philosophy of Objectionism. As I explain in Disciples of the Mysterium, I object to the fact that the world is full of ideas which should have remained undisclosed. The world would have been a far better place, and far more enriched, if the term Hermetic was understood and honored.

We're flooded with sacred texts and scriptures, sects, cults, yogic systems, gurus, pundits, hymns, prayers, mantras, speeches, doctrines, drums, bells and tamborines. No bloody silence.

Wisdom of the heart remains intact as long as it is kept within the heart, not sold cheap on the street corner.

We've defaced truth by way of our leaky brains and idle tongues. We've filled the planet with our cacophony. We've placed high-powered explosives in front of Aladdin's Cave, blasted it open to the winds, and ransacked the place. Instead of the heavy silence of the sanctum, we prefer the crowded market-place full of howls, shrieks, cavorting and intoxication. As Heidegger says, Being, the darkest of all terms, has abandoned us. Our very call to it turns it away forever. No wonder!

After all, what do we learn from I think, therefore I am? Why could Descartes not have kept it to himself? It's really about his beinghood anyway. Why were the words Know Thyself, written at the oracle of Delphi? Has it done anyone any good? Why couldn't people work it out for themselves? Because, obviously, that's the hard part. Writing or saying it is damned easy. Hence the appeal.

|

|

Silence is better than unmeaningful words - Pythagoras

|

|

|

Oh, what untold riches we've lost along the way. What impoverishment by way of words.

|

|

|

|

Whoever cannot find a temple in his heart, the same can never find his heart in any temple - Mikhail Naimy

|

Too bad no one told you that you have no obligation to share a profound thought or experience with another, at least not in words. When and if one is moved to speak their heart, let them do so in music, art, poetry or drama. It makes for high art, and we could do with it once again. Otherwise, be silent and let the silence speak. It has plenty to say.

. . .

Michael Tsarion (2021)