We're Talking Heroes!

.

by Michael Tsarion

|

|

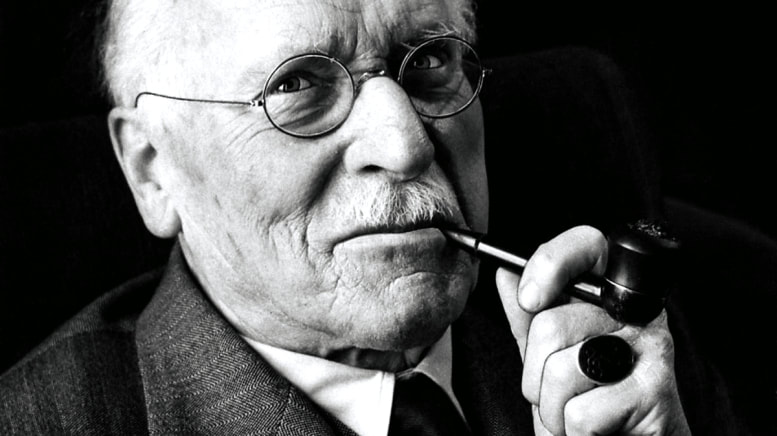

The hero symbolizes a man’s unconscious self, and this manifests itself empirically as the sum total of all archetypes and therefore includes the archetype of the father and of the wise old man

- Carl Jung |

|

|

|

Who were Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph and Judah? Who were Samuel, Saul, David and Solomon? And who were Jonah, Samson, John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth? More importantly, what were they?

Almost every major celebrated character mentioned in the Testaments are archetypal heroes. And it's not just coincidence? Each heroic character has at least one adversary fulfilling the role of villain or antihero, which is why the various stories of the Bible are so captivating to so many readers and believers, so thrilling and epic. Although the various heroes appearing in history and mythology encounter different challenges and tasks, they frequently find themselves confronted by a powerful adversary. According to Carl Jung, the hero gets to be a hero by facing and defeating a devilish human or fearful monster of one kind or another. It's a very old motif, two examples of which are found in the myths of Gilgamesh, Hercules and Beowulf. Without analyzing each and every world myth and historical account, we ought to contemplate Carl Jung's core message about heroic figures, in whatever guise they appear. According to Jung, the hero is but one "archetype" deeply affecting human consciousness. It appears as a dominant archetype in the psyche because it physically appeared throughout the course of human history, leaving a deep imprint on the consciousness of every man and woman. Some would say that the hero isn't only a "part" of history, but that he is history. Certainly in every country and continent we have the figure of the brave warrior and intrepid adventurer. We have the nonconformist and outsider, the man who did things his way, despite the norms and dictates of society. Over the course of historical time, humanity's experiences and impressions of this type get installed in the psyche. As the impressions constellate they gain in power, eventually forming what Jung referred to as the Animus, a word that also connotes the soul. Indeed, when all is said and done, Jung thought of the Animus and its counterpart, the Anima, as hemispheres of the soul. No human being can do without them, and no consciousness exists without these and other archetypal imagos. |

|

|

|

Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961), warned that the fall of civilizations is caused by psychic disharmony. The most important psychic constituents he named the Anima and Animus. Other "archetypes" work to help the two primary polarities properly integrate. Pathology occurs when this process breaks down. When one polarity turns malignant, its counterpart follows suit. The negative Animus complex radically disaffects the feminine and the female, and vice versa. (Here for more...)

|

|

|

|

There are at least a dozen important archetypes making up the psyche. Along with the Anima and Animus we have the Warrior, Wanderer, Orphan, Innocent, Trickster (or Fool), Wise Man, Wild Man, Outsider, Shadow and Devil. One can also rightly add the Martyr (or Wounded Hero) archetype to the list, given that it's an important type for males. Jesus is often presented as an archetypal Martyr, as many elements of his life-story confirm.

The Jesus story captivates the imagination because it encapsulates most of these archetypal figures in a single character, which suggests that the story is just that - a story, rather than the account of an actual historical individual. Jesus is but one of numerous heroic "sun-kings," as a close unbiased study confirms. The Jesus story contains many elements found in the sagas of Mithra, Ahura Mazda, Zoroaster, Osiris, Horus, Attis, Dionysus, and many other iconic figures from ancient cultures. In psychological terms, humanity's everyday experiences of heroism constellated over phylogenetic time to form the idea of the hero. And ideas most definitely shape our thinking and world. The Animus exists in each man and woman, constituting masculine proclivities, tendencies and characteristics. It is particularly active in magnanimous people with an assertive, forthright, optimistic character, and a never-say-die attitude toward life's challenges. This type's presence inspires others to action and success. They are confident, motivated and tireless. They seek out challenges and aren't dissuaded by hard work and occasional failures. As the great myths reveal, the outstanding heroic Alpha Man is primarily defined by the way he takes on the forces of evil. The higher Animus-figure finds himself confronted by evil, and his tireless efforts to overcome it define his personality more than anything else. Indeed, the hero is the only thing feared by evil. As far as Nietzsche was concerned, without the heroic type there could be no such thing as civilization. However, after toiling to lay the foundations of civilization, the hero soon finds himself superfluous, if not obsolete. Normal societies find him a nuisance and conspire with one another to rid themselves of his magnanimous fearless presence. |

|

|

|

The Magnificent Seven, the Western based on Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo, stands as one of the best illustrations of the Animus archetype in its many guises. There are many other popular movies dealing with the subject, implicitly or explicitly. This movie perfectly expresses the philosophies of Plato, Hegel, Carlyle and above all Nietzsche. (See "Great Man Theory")

|

|

|

|

According to Jung, the two most important archetypes are the Animus and Anima, the masculine and feminine polarities of the psyche. Given the plethora of love-scenes and boy-meets-girl scenarios in literature and film, he must be right. Neither Anima or Animus can be thought of except in relation to one another. From early romantic renditions - such as Tristan and Isolde, Diarmid and Grainne, Heloise and Abelard, and Lancelot and Guinevere, etc - to later versions like Romeo and Juliet, we find the eternal dyad working itself out. The resolution of their complex interplay? - the Self in all its greatness and splendor.

For a child, the dyad appears in the form of mother and father. Later, when boy meets girl, it appears again in all its glory. But earlier than this, in a infant's innate Will-to-Power and zest for existence, we find the influence of the Animus. The effort it takes for a fetus to push through its mother's birth canal, constitutes the earliest manifestation of masculine energy. The roar of a newborn grotesquely turned upside-down and spanked also marks the first instance of righteous anger, a trait absolutely associated with the Animus. In a more sophisticated context, the Animus directs us to remain assertive, self-possessed and future-oriented. It undergirds the Will-to-Meaning which won't be satisfied simply by physical and material successes. Without the Will-to-Meaning, life would be easier but dull as heck. Think of the world without high art, music, poetry, architecture and necessary scientific inventions. Think of yourself without curiosity, inspiration, aspiration, dreams and goals. All your minor and major achievements are due to the presence and influence of the Animus, as is your very sense of personal identity. Jung stressed that we are not to think of the archetypes as foreign entities, because they are quite literally parts and pillars of the Self. They can work in harmony, but for most of our lives they interact conflictually. If they did not, we'd have no reason for living. What we call life is the process by which the many archetypes strive for homeostasis. This is especially true of the Animus and Anima. Indeed, every person (or stereotype) encountered on a daily basis, plays a part in the mysterious archetypal drama. Without the Anima and Animus, there's no question of empathy, humanity, sociability, friendship or "falling in love." Part of the complex integration process involves searching for the influence of the Animus externally. It's why as children we looked to this and that pop-icon or movie-star for inspiration and guidance. It's a natural tendency and we'd be lost without it. Freud referred to the mind's natural image-making capacity as the ego-ideal, and stressed its importance. The word ideal refers directly to admired iconic individuals who serve as guides leading one toward the attainment of their own true identity. In other words, there is within each person a natural inclination toward heroism. If it's difficult to detect, it's only because its been suppressed, probably by clueless parents or a feminized society. |

|

|

|

I cannot think of any need in childhood as strong as the need for a father's protetion - Sigmund Freud

|

|

|

|

The ego-ideal is especially useful if it turns out that our parents are not seen as healthy imagos. If neither of them are authentically heroic, a child's mind naturally turns to other people for what is needed. We turn to members of our wider family, hoping that some grandparent, uncle, cousin or family friend suits our semi-conscious requirements. If they too are found wanting, we often seek out heroic figures in history books and the media. In fact, famous people are often famous precisely because they easily receive our archetypal projections.

In certain cases, before we leave the Oedipal Stages, we might even find surrogate non-human imagos representing heroism. This is the reason, for example, why young girls tend to adore horses. The obsession arises when and if there's a lack of heroic stereotypes and archetypes at home and in school. |

|

Girl without heroes at home

|

|

The lack of external heroes is devastating for the psyche. As said, the ego-ideal must locate and introject healthy heroic imagos if sanity is to prevail. If the search fails for any reason, the ego-ideal may eventually start focusing on transgressive figures, and anti-heroic imagos are likely to get installed instead.

It wont be too difficult for this to happen, given how many anti-heroic supervillains are featured in today's media. They proliferate on TV, and in ads, comics and video-games. They are found in plenty in most movies, and are no longer summarily overcome by the man in the white hat. Today's film-makers relish having evil characters come out on top. In the horror genre, we find monstrous figures returning from the dead again and again. It is true to say that today's societies prefer that the consciousness of the young is shaped by unhealthy imagos. |

|

|

|

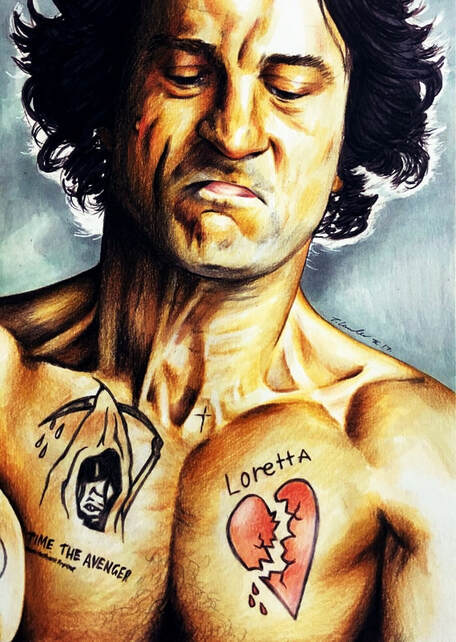

The transgressive figure or imago often works as a manifestation of the Animus in its dark guise. This occurs because, historically speaking, the dark evil character was also experienced by our forebears. In every land there was the demagogue, tyrant, criminal, betrayer, liar and trickster. Because of this the psyche was imprinted by the racial memories of highly ambivalent Machiavellian Jester, Playboy, Rogue and Devil types.

|

|

|

|

Robert De Niro as the devilish psychopath, Max Cady, in Martin Scorsese's excellent psychologically-toned remake of Cape Fear.

|

|

|

|

The anti-hero is often portrayed in literature and film as a psychopath or heartless maniac. He's the killer, sadist, rapist and thief. He's Fagin, Svengali, Dr. Caligari, Professor Moriarty, Emperor Ming, Darth Vader, General Zod, Thulsa Doom, Max Cady and the Joker. He appears in numerous other guises, and for all his darkness he's a rather captivating character. In many dramas he's actually more interesting than the main goodly protagonist.

In terms of racial memory and the combat myth, he's the monstrous or Machiavellian adversary to be outwitted or destroyed by his goodly nemesis. Remember, there can be no hero without the anti-hero, no Jacob without Esau, no Baptist without Herod, no Jesus without Pontius Pilate and no Yahweh without Satan. |

|

|

|

In high art we often find that the good is occasionally compelled to work with evil to establish a higher order. Paradoxically and problematically, evil often holds the keys to one's deliverance.

|

|

|

|

The psychodrama in which the anti-hero is defeated is part of the great Individuation Process brilliantly delineated by Jung. The struggle between rivals represents the tense interplay between opposites within the psyche.

Jung's entire psychological system rests on this compensatory nature of the psyche. Each hemisphere and archetype faces its opposite, but the polarization isn't necessarily a bad thing. It's present in every neuron, cell and star, and makes a mind what it is. Psychic dynamics are a response to the underlying ontological restlessness (or Contrarium) goading us to become something more that what parents and society dictate and expect. To achieve a truly heroic state of being, and correctly overcome evil, one must know evil's ways. This is the supreme reason for the sacred power and authority of the Animus. Without being able to access the cache of deep bioenergy within the Self, one has no chance of summoning the power needed to overcome evil forces. Evil always depends on our systemic bioenergetic weakness. Most people cannot sustain their Will-to-Power or Will-to-Meaning. It's easier to give up, give in and recoil from life's many challenges. From childhood on we are faced with doubts, fears, phobias, anxieties, frustrations and worries. We leave the family unit and quickly realize we're not invulnerable, mighty, precious and irresistible. We soon encounter the vexing boy or girl who is simply better, and are forced to deal with hefty blows to our egos when bested. It's all too much for feminized docile bodies unwilling to abandon the Pleasure Principle and Magical Child Thinking. The Animus is the force keeping us going despite the harangues suffered in the family and in society. However, heroism isn't just defined by how many challenges stand in our way. It's defined by how we negotiate and overcome them, and if we come out the other end sane, aware and true. The Animus not only directs our physical will but also our intelligence. It not only directs a Genghis Khan, but also a Sherlock Holmes type. Indeed, without the Animus operating in its higher mode, there can be no victory over evil. Where a balanced Animus is found, evil cannot be. |

|

Evil-Free Zone

|

|

Society everywhere is a conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members - R. W. Emerson

|

|

|

|

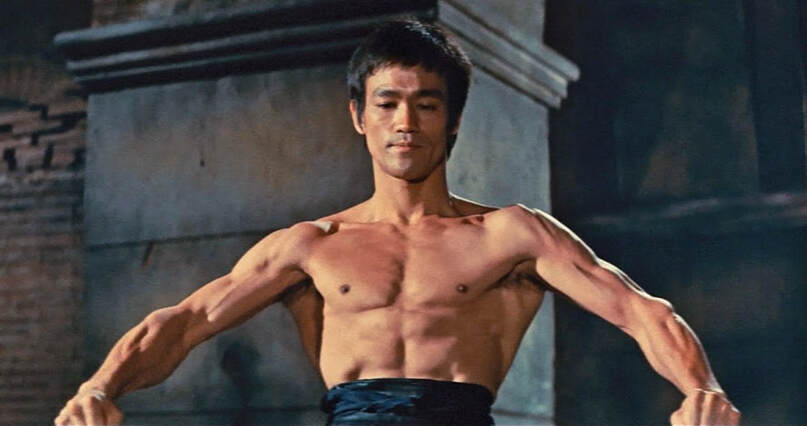

Along with the problem of the evil nemesis, we have the dilemma of the inflated Animus. Indeed, as Jung showed, each of the archetypes can suffer from bouts of grandiosity and self-importance. This syndrome occurs when chances for correct integration have been missed or rejected. It's the condition that prevails today among most men and women. Most manifestations of the Animus today are in its inflated mode.

Strangely, the anti-hero's appearance, although threatening, often assists in the healthy development of the Animus, presenting crucial elements which the Animus must integrate at all costs. The adversary's presence and influence occasionally helps restore the Animus to its true proportions. It knocks the inflated ego down to size, assaulting, robbing and wounding the Animus in order to reinstantiate a sense of proportion. Speaking of typological dilemmas, we find that it is common for a healthy Animus expression to be conflated and confused with what I refer to as the Chivalric type, a rather preposterous testosterone-saturated male who has suppressed his authentic feminine side in order to come across to others as stalwartly male. Of course, this "superhero" type is really little more than a caricature of masculinity. Sadly, this extrovert type lives a long life without realizing what an imbalanced soul he is. Moreover, he occupies a society that aids and abets his false "hard-bodied" persona by over-valuing and rewarding his type immensely. In Reichean terms, the inflated Animus closely corresponds with the "amored" type. One thinks of Sir Lancelot, the hero who falls in lust with his king's unfaithful consort and commits the ultimate sin. But what Reich sought to define is the personality type who shrinks from being heroic in any authentic sense. The armored type is characterologically insensitive and unable to conquer either the evil in himself or the world. He finds inner conflict too difficult to deal with. Pathologically hating himself for feeling, he soon decides to shut off feeling completely. He turns his body into a cage of sorts, tightening his musculature to prevent his organism from freely expressing any kind of natural feeling. He concentrates on physical achievement and takes refuge in his frontal lobes. He prefers intellectual prowess and conquest over emotionality, even though he's quite capable of displaying contrived histrionic emotions when it suits him, such as when he's defending a cherished cause or ideal. His macho persona is nothing more than an act concealing anxiety about his dire inner condition. Reich knew it was all bluster, baloney and compensation. He understood that the world's fixation with muscle-men and muscle cars, gadgets, machines, digital technology, competitive sports and other displays of faustian will is all in service to the mutilated Animus that once operated in accordance to natural law. He understood that the unbalanced inflated armored Animus is one of the main causes of evil in the world. |

|

|

|

The hero’s main feat is to overcome the monster of darkness - Carl Jung

|

|

|

Indeed, the higher Animus does serve nature, whereas the perverse or "daemonic" Animus does not. It serves the faustian Will-to-Power satiated by raw competitiveness and worldly success. There is no better ally of evil than the armored personality type. As philosopher Ayn Rand wisely stated "...the man who fails to see evil as evil soon finds it impossible to see the good as good."

As Jung shows, there can be no healthy Animus without positive heroic imagos, which tend to be in short supply in today's society. What we find ourselves installing in the psyche are broken, inflated or feminized imagos, which in turn work to pathologize self and society. In the near future, it is not impossible that we'll find ourselves living without the positive Animus making an appearance. We'll have no masculinity, manhood, heroism or courage, and therefore nothing we can with a straight face call sanity and civilization. |

|

. . .

Michael Tsarion (2020)