Schopenhauer’s Error

.

by Michael Tsarion

|

|

Every high culture is a tragedy - Oswald Spengler

|

|

|

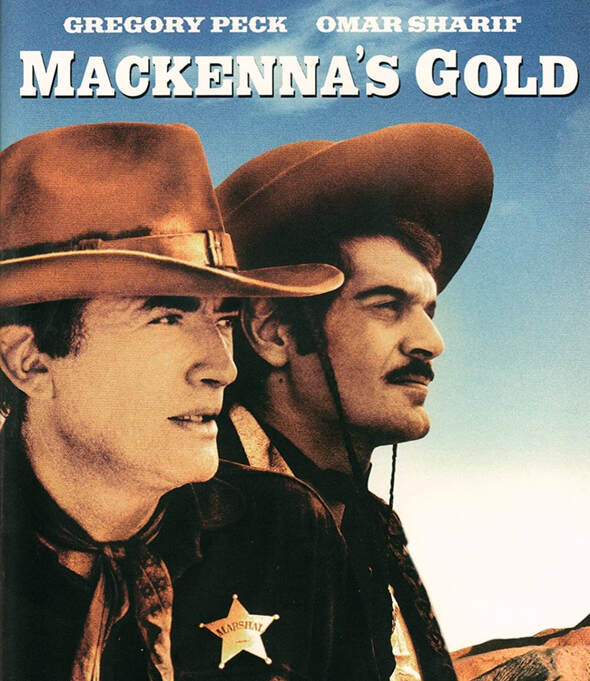

In Mackenna’s Gold (1969), we get a drama obliquely exploring why we need the phenomenon we call “civilization.”

The adventure involves a map in the keeping of an old dying Indian chief, showing the location of a lost valley - the Canyon del Oro - containing millions in pure gold, enough to make its finder richer than anyone ever. As the movie progresses we find out that far from being a secret, several people, from all walks of life, know about the map’s existence, each intent on getting their hands on the treasure. After the death of the old chief, the main protagonist, Marshall Sam Mackenna, soon finds himself surrounded by all sorts of oddballs out for the gold, eager to accompany him on the difficult journey to the hidden canyon. Among these characters we have a wily card-shark, a bored shopkeeper, a cantankerous preacher, an old blind prospector, a ruthless bandit, a self-serving cavalry sergeant, and two hapless English adventurers out to make their fortunes in the New World. Possessed by gold-fever and mesmerized by the promise of vast riches, they agree to co-conspire only to attain personal ends. Since the journey to and discovery of the legendary canyon is bound to be long and perilous, Mackenna is forced against his will to accept that the apparent liability of "too many cooks" might turn out to be an asset after all. |

|

|

|

The movie serves as a perceptive comment on Nietzsche’s Will-to-Power, by which civilizations come about.

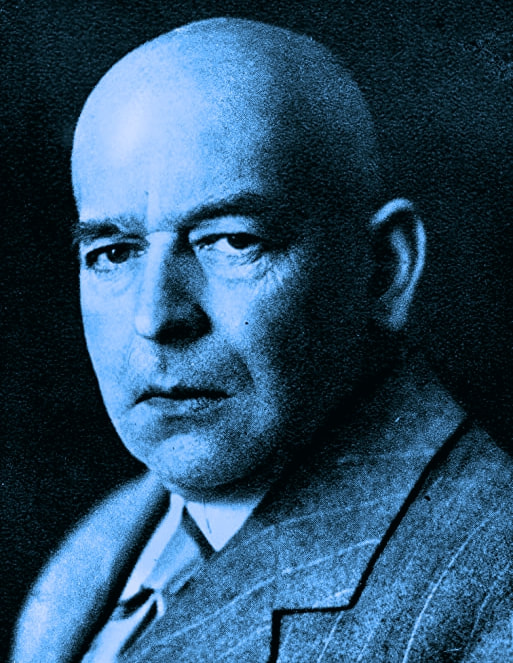

The premise is forced collusion, given that it is axiomatic that despite one's intent, one's will cannot have its way without eventually encountering obstacles. The will is not wholly free. There are boundaries and restrictions within and without, preventing the attainment of what we think we desire. Nietzsche stressed that the personal will is chiefly obstructed by the wills of others. This sets up a peculiar paradox, because although each person desires complete freedom of the will, desire itself makes this impossible. To describe the Will-to-Power we need only imagine a variation on the story of Ali Baba. If I find myself unable to shift a great boulder blocking my way into a cave full of gold, silver and precious jewels, I find myself reluctantly but inevitably seeking the help of other people. It’s not my core desire, but circumstances demand I not only recruit helpers, but also share the cave's booty with them. I benefit when and if others also benefit. For this reason, selfish desires are sublated and I find myself conspiring with others to achieve mutual goals. This is the origin of tribes, communities, gangs, politics and wars. Without the collectivized Will-to-Power there can be no Mitwelt (or society). In other words, the coming together of many wills gives rise to what we know as civilization. Any critique of civilization, as we find in the philosophies of Schopenhauer, Evola, Spengler, Nietzsche, and others, is therefore also a critique of the Will-to-Power by which civilizations come to be. Nietzsche’s theory developed out of the pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. Both men's outlooks were in turn reiterated by numerous later thinkers. One of these was the great German historian Oswald Spengler. He reiterated Nietzsche’s ideas in his works, one of which is his essay Man and Technics. In this important work we find key themes and ideas later reprised by Martin Heidegger and other existentially-minded thinkers. |

|

Oswald Spengler (1880-1936)

|

|

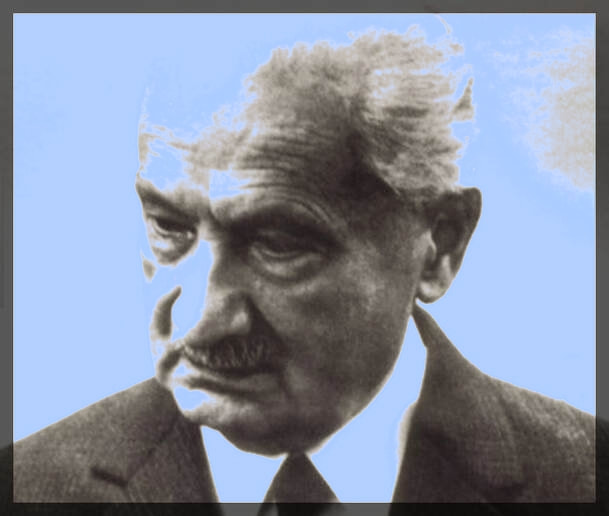

Like Gabriel Marcel, Gustave Le Bon, Sigmund Freud, Otto Rank, Oswald Spengler, and others, Heidegger was interested in the sociopolitical manifestations of the Will-to-Power. He realized that Crowd Consciousness is a conspicuous example of it, as is political activity.

With Schopenhauer specifically in mind, Spengler honed in on the underlying reason for the Will-to-Power and effort of humans to construct civilizations. As Schopenhauer emphasized, nature must be regarded as man’s first and foremost enemy. As far as he was concerned, nature has no essential purpose or meaning. It is blood red in tooth and claw and if any “will” moves through nature, it is blind, sick, perverse and purely evil. Schopenhauer eloquently extrapolated on this bleak outlook at length in works which captivated and challenged the minds of many great Continental thinkers. Heidegger’s work is, for the most part, a deep critique of ideas expressed by Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. From Being and Time onward he set out to examine every aspect of civilization, and how they come to be via the collectivized will. The human inhabiting a civilization based on antipathy to nature he refers to as Das Man; he who submits his personal Faustian will to that of the many. By doing so, Das Man (“The One”) still expects his own needs to be met. He’d prefer to satiate himself more aggressively and immediately - by acts of brute force, rape, murder and theft, etc - but is compelled to realize that by doing so he is bound to come up against obstacles that are often insurmountable. He comes up against police, laws and the harsh judgements and penalties of society. He also comes up against the prohibitions of his own conscience, which steeps him in shame, sometimes forever. |

|

Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), the sage of Messkirch

|

|

The key point was pointed out by Nietzsche; one's Will-to-Power clashes with the will of others, forcing one to begrudgingly cooperate with them.

In other words, something paradoxical takes place when one is a disciple of the Will-to-Power. That which animates the subject eventually becomes collectivized, driving him to collaborate with those who, on the primitive level, start as rivals and threats. Thus, will changes by way of will. Circumstances alter the nature of the will which for practical purposes partially yields to that which it despises - nature and the Reality Principle. Reluctantly yielding to reality, the will works overtime to find circuitous routes to its satiation, one of which entails collusion with others. Hence the advent of the general will and common purpose. From this point onward the human will, as transformed and transmuted by the Natural Order, irrationally works to subvert the order that gave it birth. Spengler focuses on the Will-to-Power’s primordial antipathy toward nature, emphasizing that it is nature’s power that humans resent. In this sense, the Will-to-Power is ultimately humanity’s reaction to a power it cannot control, and which can overwhelm humanity at any given point. Das Man does not normally contemplate the awesome power of nature, or understand how their non-conscious antipathy toward nature lies at the base of his waking consciousness. We are not aware of why towns, cities, bureaucracies and political parties exist, and that they insulate us from nature. Nor do we question why we live in largely artificial hives in which abnormal hierarchies become all-pervasive, facilitating the raw Will-to-Power by which one person or group gets to rule and control others. As Heidegger and Spengler show, the societies man labors to establish in turn transform the individual. In effect he becomes an anti-individual - a mere "subject" whose consciousness is little more than a social pastiche. From within his urban gulag, the subject keeps the abjected forces of nature at bay. Recast as a busy, engaged participant in city-life, Das Man quickly attaches himself to other people with similar ideas and intentions. To maintain the facade, he and his fellows constantly concoct this or that all-important project to absorb their minds and energies. Deafened by the cacophony of their myriad enterprises and tasks - their science and technology - they've no time to address their inauthenticity and infatuation with nonsense. The urbanized subject preoccupies himself by decorating his prison. The results of his industry - of the collectivized Will-to-Power - are seen all around us in the form of the many hierarchies, clubs, groups, cliques, parties and mass movements. And should Das Man one day find himself bereft of "meaning," he can always seek solace in a suitable made-to-order religion expounding yet more anti-natural supernatural propaganda. Heidegger and Spengler believed that the Will-to-Power not only expresses itself in the construction of towns, cities and civic bureaucracies, but chiefly in technology. The phenomenal advancement of technology and its products indicates that it serves the necrophilous anti-natural will of man. In this regard, their thought is very close to that of the English mystic and poet William Blake, who also regarded technology as the chief means by which humanity incarcerates itself in anti-natural environments. For Blake, however, it is not only nature's power that offends man, it is also its mystery. Technological advancement is, however, not the solution we imagine it to be. Civilization, says Spengler, is terminal. Born from our irrational antipathy to the Natural Order, it leads to apollonian heights at the cost of losing our roots in reality. The further we “progress,” the further we estrange ourselves from nutrients essential to Being. Although we build our house of cards high, it is bound to fall at the slightest breeze. At first, in early times, man’s will found itself subordinate to nature. Nowadays, due to its unparalleled advancement and complexity, we find ourselves subordinate to technology. |

|

King Canute

|

|

All things organic are dying in the grip of organization. An artificial world is permeating and poisoning the natural - Oswald Spengler

|

|

|

|

Like Blake, later thinkers such as Ralph Emerson, Rainer Maria Rilke, Friedrich Holderlin, Owen Barfield, Gabriel Marcel and Martin Heidegger, understood that what really irks man about his relationship with the natural world, is nature’s mystery.

This numinous negentropic Mystery transcends rational understanding. It cannot be circumscribed, categorized, catalogued, shelved or put on display. It’s not a manifestation of human intellect, as Descartes and Kant believed. It’s not something to be entrapped by mind. Consequently it has been made into an absolute other. This irrational attitude is exemplified by Schopenhauer, who failed to see that it is not nature itself that is evil in any way, but man's thinking about nature that is. |

|

|

|

...for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so - William Shakespeare

The real Maya or illusion is not in the natural forms, but in the mind’s propensity to conceive or project forms created by its own inventiveness, but which do not agree with the truth extant or potential in nature - Alvin Boyd Kuhn |

|

|

|

Ironically, despite humanity’s deep antipathy to the power and mystery of nature, human civilizations must be constructed using natural materials. Once this was begrudgingly acknowledged, the Faustian will envisioned the natural world simply as a commodity and resource. Although nature is exploited for its wood, stone, ivory, fur, scent, ore, minerals, flora and fauna, etc, man denies any debt to nature. It’s just “stuff” to be used in the construction of the human world, the planet just some recreational theme-park of sorts to enjoy and exploit. Nothing in it - no stone, flower, tree, mountain or animal - experiences anything. That’s only for humans, right?

|

|

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

|

|

…the lord of the world is becoming the slave of the machine - Oswald Spengler

|

|

|

|

For Spengler, and thinkers of his type, urbanization is man’s attempt to insulate himself from the Natural Order. The Schopenhauerian and Nietzschean Will-to-Power need not learn from nature, and does so only to appropriate and secure nature's resources for practical usage. We learn from nature’s ways only in so far as it enables us to create civilization as a simulacrum of reality and nature’s supreme mystery. It’s a case of “horse-power” not horses.

|

|

|

|

Hobbes describes the Leviathan as akin to a form of “artificial life” artfully designed by the rational faculty of man in order to imitate the work of Nature - Jason Jorjani (Iranian Leviathan)

|

|

|

|

The process of civilization-building stands as credible only while we embody Schopenhauer’s erroneous vision of nature and will. His hostile attitude toward the real has made it possible for the Faustian will of humanity to become even more necrophilous and inhuman than it was before the rise of civilization. It has made it possible for us to erect corrupt unsustainable hierarchies throughout civilization, so metaphysically weak they cannot hope to continue casting shadows over the world, ad infinitum.

In Man and Technics, Spengler warned of inevitable future fallout. The latest tech devours the previous tech. Knowledge and truth disappear under an avalanche of information, and we end up knowing least about what matters most. Kids and teens are so embedded within the simulacrum and so hyper-mechanized that they’ve lost every trace of humanity. Ironically, technology, no matter how sophisticated, can’t hold them together. Das Man is now invalidated by his own systems. He inhabits apollonian heights from which he cannot afford to fall. Our age-old desecration of nature means we’ve destroyed the ground we'll need to break our fall. There’ll be no Natural Order to cling to once the teetering tower of technological humanity explodes and falls. Subconsciously, every person knows this to be true. Do they then turn from the Will-to-Power? Do they give it up in favor of the Will-to-Meaning? No! Despite numerous warnings, modern man continues on his journey toward oblivion, driven by his insatiable Will-to-Power. Das Man adjusts his attitude alright, but not in a healthy reverent way. He decides that since he's fighting the clock he’ll simply live for today. Since oblivion looms, he must get what he wants immediately. Hence our one-click, push-button, drive-thru, big-gulp, sound-bite culture. Modern logic dictates that if the cliff’s edge approaches, I'd better get my kicks and highs in while I can. If Achilles did it, so can I. If he preferred a short life of glory, success, fame, flowers and speeches, it’s good enough for me...good enough for all. Right? |

|

. . .

Michael Tsarion (2020)