THE FIRST

PHILOSOPHER

.

By Michael Tsarion

|

|

There is pleasure in the pathless woods, there is rapture in the lonely shore, there is society where none intrudes, by the deep sea, and music in its roar; I love not Man the less, but Nature more - Lord Byron

|

|

Being in the world means experiencing the world of objects and entities. This much we know. What is less recognized is that in each and every experience we also experience ourselves as experiencers.

The world we know always reflects back to us an image of Self. There can be no experience in which a sense of Self is not on some subtle level apparent.

This phenomenon is important because it constitutes the origin of philosophy.

Philosophy began when someone became vividly aware of themselves as experiencer. Most people live out their entire lives lost in experiences, without once reflecting on this mystery - for mystery it is.

What else merits contemplation?

The world we know always reflects back to us an image of Self. There can be no experience in which a sense of Self is not on some subtle level apparent.

This phenomenon is important because it constitutes the origin of philosophy.

Philosophy began when someone became vividly aware of themselves as experiencer. Most people live out their entire lives lost in experiences, without once reflecting on this mystery - for mystery it is.

What else merits contemplation?

|

|

Isn't it interesting that not only do you have all these thoughts running through your mind, but you are able to stand outside of them and observe them? When you observe them you become an object of observation within yourself. This ability to stand outside of yourself and observe yourself thinking points to an “observing “observing you” outside of your thoughts - Albert Linderman (Why the World around You Isn't As It Appears)

You exist as both a subject and an object: a subject when you think of something other than yourself, and an object when you think about yourself - ibid |

Think of the all-important gateway questions of philosophy - Who am I...What am I doing here...Where am I going? Has anyone sensibly answered these for themselves?

Whether they have or not, the greater mystery remains. How is it possible that I come upon myself as experiencer via the world of experience? In other words, what do I actually know about that thing I call "World?"

Not very much said Martin Heidegger. No much at all.

Acting in the world, and having myriad experiences returns us to ourselves. We have two encounters, one with Self and another with World. We don't normally bring the intimate reciprocal relationship between them to consciousness. Why is this?

You certainly do not acknowledge that the person you take yourself to be is an emanation of the World. No! The world after and beyond this one gets far more attention for some reason.

Whether they have or not, the greater mystery remains. How is it possible that I come upon myself as experiencer via the world of experience? In other words, what do I actually know about that thing I call "World?"

Not very much said Martin Heidegger. No much at all.

Acting in the world, and having myriad experiences returns us to ourselves. We have two encounters, one with Self and another with World. We don't normally bring the intimate reciprocal relationship between them to consciousness. Why is this?

You certainly do not acknowledge that the person you take yourself to be is an emanation of the World. No! The world after and beyond this one gets far more attention for some reason.

|

|

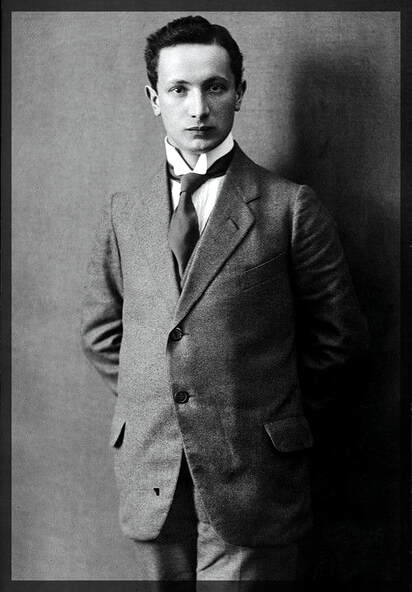

Martin Heidegger (1889-1976). Following closely the poetry of Holderlin and Rilke, he made nature a central theme, particularly in his later work.

|

|

The first person who engaged in this Self-reflexive contemplation learned to observe the world in a completely different way than his fellows. He learned to look at himself differently too. He was the first philosopher.

Via the mirror of reality - of the World - he turned within to ask who is this me standing here amid the world experiencing, observing and being aware I do so?

Normally, this level of awareness doesn't bother anyone. We skip over the primordial relationship with World in our haste to get to relationships with other people. That's the world we know and prefer. As Heidegger emphasized, the primordial encounter with World isn't important for us. It's rendered invisible by proximity. It's just the place we find ourselves in. Nothing to notice and inquire into.

The Existentialists, like Heidegger, downplay the significance of the so-called "unconscious mind." So much of what lies in front of us is already blocked out of sight and concern, why bother about the the depths of the unconscious? The very pavemnent on which I walk isn't part of my conscious awareness. Like the glasses on my face, the back of my body, the handle I turn to enter a room, the pedals in the car I drive, and so much more isn't "there" as I glide through the world. What else do I not see and know?

Is it all down to Darwinian evolution? Unless I edit what there is to experience, I won't be able to effectively function in life. Okay, maybe so, but the question still remains as to which part of me acts as the executive censor, deciding what gets registered and what does not?

Heidegger's worry was that by overstepping the Self-World encounter, we'll enter society (Mitwelt) as fundamentally impoverished beings. This type of person he called Das Man, the grey nondescript conformist whose relations with others are existentially inauthentic.

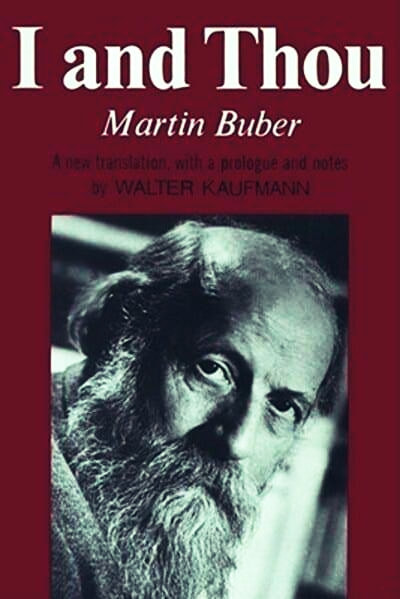

Martin Buber disagreed, and put great emphasis on human to human interaction, regardless of its characteristic banality.

Buber prioritized the I-Thou engagement, and mildly criticized Kierkegaard, Heidegger, and other thinkers for not putting it first in their teachings. As Hegel had first emphasized, the mystery of Self-consciousness is paradoxical, because in order to fathom it I must enter into relationships with other people. Apparently, the mystery of myself lies in the eyes of others.

Via the mirror of reality - of the World - he turned within to ask who is this me standing here amid the world experiencing, observing and being aware I do so?

Normally, this level of awareness doesn't bother anyone. We skip over the primordial relationship with World in our haste to get to relationships with other people. That's the world we know and prefer. As Heidegger emphasized, the primordial encounter with World isn't important for us. It's rendered invisible by proximity. It's just the place we find ourselves in. Nothing to notice and inquire into.

The Existentialists, like Heidegger, downplay the significance of the so-called "unconscious mind." So much of what lies in front of us is already blocked out of sight and concern, why bother about the the depths of the unconscious? The very pavemnent on which I walk isn't part of my conscious awareness. Like the glasses on my face, the back of my body, the handle I turn to enter a room, the pedals in the car I drive, and so much more isn't "there" as I glide through the world. What else do I not see and know?

Is it all down to Darwinian evolution? Unless I edit what there is to experience, I won't be able to effectively function in life. Okay, maybe so, but the question still remains as to which part of me acts as the executive censor, deciding what gets registered and what does not?

Heidegger's worry was that by overstepping the Self-World encounter, we'll enter society (Mitwelt) as fundamentally impoverished beings. This type of person he called Das Man, the grey nondescript conformist whose relations with others are existentially inauthentic.

Martin Buber disagreed, and put great emphasis on human to human interaction, regardless of its characteristic banality.

Buber prioritized the I-Thou engagement, and mildly criticized Kierkegaard, Heidegger, and other thinkers for not putting it first in their teachings. As Hegel had first emphasized, the mystery of Self-consciousness is paradoxical, because in order to fathom it I must enter into relationships with other people. Apparently, the mystery of myself lies in the eyes of others.

|

|

The fundamental fact of human existence is man with man. What is peculiarly characteristic of the human world is above all that something takes place between one being and another, the like of which can be found nowhere in nature - Martin Buber

The central subject of this science is neither the individual nor the collective but man with man - ibid |

|

|

|

Martin Buber (1878-1965) emphasized the "dialogue" between people in society as the key to finding meaning. He addressed the paradox first delineated by Hegel, that the secrets to the mystery of Self-consciousness lie in the eyes of others. It is not correct, therefore, to run away to caves to find the truth. The hermetic life does not lead to meaning. Thus, Buber was not in favor of concepts such as the Outsider, as described by Existentialists. Although Mitsein, or "being-with," was essential for Heidegger, Buber wishes it was more robustly articulated.

|

|

Heidegger's concern, however, is the kind of person I become, entering the Mitwelt without first being deepend and enriched by the originary all-important encounter with World, which truly contains the essence of my identity. In my haste I overstep that encounter and regard World as simply somewhere I find myself. It's merely a banal backdrop to my everyday experiences. I place importance solely on these experiences, not on myself as experiencer. That plays no part at all, and rarely enters my head.

How, asks Heidegger, can philosophy be based on anything other than this originary symbiotic participation between Self and World? His entire philosophical corpus is dedicated to observing and describing this encounter. What does it matter if two humans meet and "dialogue" if both are existentially uprooted and "uncaring" about their essence?

What comes of their interaction if both are unreflective and "ungrateful" in the deepest philosophical sense?

Das Man's encounters are functional, shallow and designed to block something deeper from arising. The cacophony of the "ontic" or everyday world drowns out the inner voice calling and directing us back to nature.

Existentialists rightly point out that although society is the mirror of the ego, nature (Umwelt) is the mirror of the Self.

However, nowadays our going to nature is not authentic. It is a recreational pursuit, not an existential one. We are uprooted and incarcerated in our urban gulags, with no intention of honoring nature. It's abused and construed as something dirty and lower. As Heidegger writes, it's just a "resource" to be exploited. And exploited it certainly is.

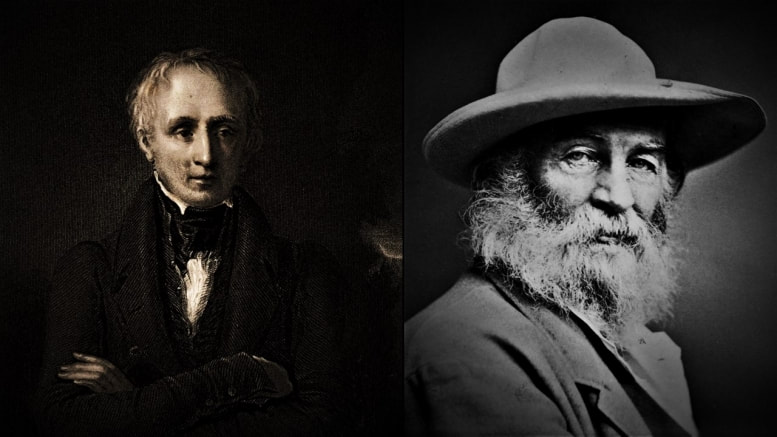

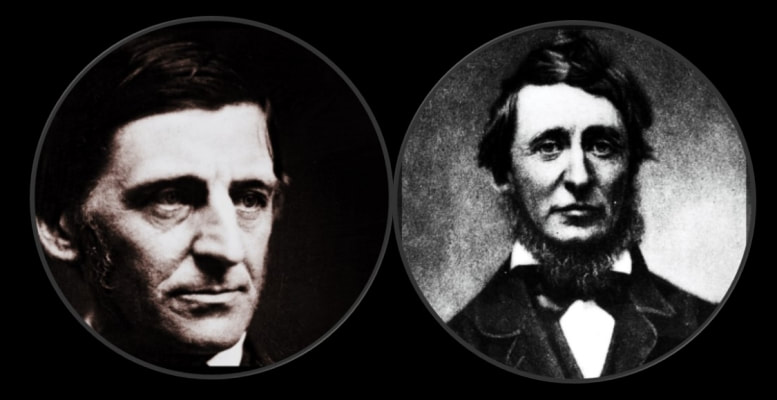

There have been a few major thinkers who have saluted nature in their works. These men include Lao Tzu, Friedrich Holderlin, Rainer Maria Rilke, William Wordsworth, Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. That's about it.

A poet or thinker can be distinguished as to their orientation. Is it toward the phenomena of society or nature?

How, asks Heidegger, can philosophy be based on anything other than this originary symbiotic participation between Self and World? His entire philosophical corpus is dedicated to observing and describing this encounter. What does it matter if two humans meet and "dialogue" if both are existentially uprooted and "uncaring" about their essence?

What comes of their interaction if both are unreflective and "ungrateful" in the deepest philosophical sense?

Das Man's encounters are functional, shallow and designed to block something deeper from arising. The cacophony of the "ontic" or everyday world drowns out the inner voice calling and directing us back to nature.

Existentialists rightly point out that although society is the mirror of the ego, nature (Umwelt) is the mirror of the Self.

However, nowadays our going to nature is not authentic. It is a recreational pursuit, not an existential one. We are uprooted and incarcerated in our urban gulags, with no intention of honoring nature. It's abused and construed as something dirty and lower. As Heidegger writes, it's just a "resource" to be exploited. And exploited it certainly is.

There have been a few major thinkers who have saluted nature in their works. These men include Lao Tzu, Friedrich Holderlin, Rainer Maria Rilke, William Wordsworth, Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. That's about it.

A poet or thinker can be distinguished as to their orientation. Is it toward the phenomena of society or nature?

|

|

Friedrich Holderlin (1770-1843), Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926). Their poetry explores the role of nature as the ground from which Selfhood emanates.

|

|

Let's go back to the gateway questions. They arose for the first time in the mind of the first philosopher, he who for the first time caught himself oberving the observed and the observer. He found his experience of a world strangely returning him to himself as a Being-in-the-World (Dasein).

If, therefore, I now ask Who am I...How did I get here...Where am I going?...I find the answers coming to me, that I am the one who experiences myself experiencing the world, that I have never been anywhere but here, and that I am going toward a deeper understanding of the primordial communion between myself and World.

Contra Buber, I also realize that there won't be too many companions along for the ride.

The first philosopher was vividly aware of himself as experiencer of World. He was acutely aware of the World as his foremost mirror. He did not spurn society, but entered it in a different way than his one-dimensional fellows. His sense of Selfhood didn't entirely depend on the approval of other people. His sense of Being wasn't solely society's product.

If, therefore, I now ask Who am I...How did I get here...Where am I going?...I find the answers coming to me, that I am the one who experiences myself experiencing the world, that I have never been anywhere but here, and that I am going toward a deeper understanding of the primordial communion between myself and World.

Contra Buber, I also realize that there won't be too many companions along for the ride.

The first philosopher was vividly aware of himself as experiencer of World. He was acutely aware of the World as his foremost mirror. He did not spurn society, but entered it in a different way than his one-dimensional fellows. His sense of Selfhood didn't entirely depend on the approval of other people. His sense of Being wasn't solely society's product.

|

|

Authentic selfhood for Heidegger is found in the nonrelationality of death, not in the love of another - Robert D. Stolorow (Trauma and Human Existence)

|

|

|

|

Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished - Lao Tzu

|

|

The natural world isn't just a vague background to our mundane activities. It's not external to our being. It is a crucial dimension of it, something to be sensitively explored and above all revered.

For Heidegger, unless this "care" (sorge) is in effect, life isn't complete. He went so far as to say that every thought one thinks must be an one of gratitude for Being.

This comportment toward World as mirror of the Self is what really puts man at the head of the food-chain, not some notion of Darwinian or Faustian superiority.

Unlike animals, we don't just exist. We are aware of something called "World." We are aware that we are aware, and have the freedom to think deeply on the meaning of life or not to do so.

We can choose, as we often do, to immerse ourselves in the world of other people in society to avoid any deeper understanding of Being. We can allow the gossip, problems, occupations and endless domestic and social roles to utterly dominate our time and attention, in order to evade the primordial encounter with the mystery of Being.

For Heidegger, unless this "care" (sorge) is in effect, life isn't complete. He went so far as to say that every thought one thinks must be an one of gratitude for Being.

This comportment toward World as mirror of the Self is what really puts man at the head of the food-chain, not some notion of Darwinian or Faustian superiority.

Unlike animals, we don't just exist. We are aware of something called "World." We are aware that we are aware, and have the freedom to think deeply on the meaning of life or not to do so.

We can choose, as we often do, to immerse ourselves in the world of other people in society to avoid any deeper understanding of Being. We can allow the gossip, problems, occupations and endless domestic and social roles to utterly dominate our time and attention, in order to evade the primordial encounter with the mystery of Being.

|

|

English writer William Wordsworth (1770-1850) was world's foremost nature poet. Walt Whitman (1819-1892) was his American equivalent. The poetry of Ted Hughes and Robinson Jeffers also merit mention in this regard.

|

|

The first philosopher encountered the mystery of Being, the moment he returned to himself via the mirror of reality. He knew his upgraded comportment was by no means an act of will. It was nothing to do with the Will-to-Power and craving to dominate nature. It came about spontaneously, without desire. That nature held within itself the essence of his identity was enough of a mystery to captivate and inspire. As Socrates first said, this wonder, awe and astonishment is ultimately the origin of all philosophy.

Because of this, Heidegger was motivated to critique the whole history of metaphysics and religion. There the focus is with supernatural realms and disembodied gods. Nothing can be proved or falsified. Great! Doesn't anyone see the absurdity of this?

Don't we realize that the loss of the original participation with nature gives rise to any number of inauthentic compensatory replacements?

We've got them in plenty. This is why, contra Buber, Heidegger was wary of prioritizing the human to human (or I-Thou) dynamic. He put the emphasis on the quality of the individuals involved. What we have in society today is banal "chit-chat," designed to help humans evade their beinghood.

If this were not the case, there'd be no urban gulags or abuse of nature. There'd be no depression, anxiety and hang-ups. There'd be no neuroses, suicides and homicides. Society would be utterly transformed. In the words of Erich Fromm, there'd be biophilic rather than necrophilic cultures.

Because of this, Heidegger was motivated to critique the whole history of metaphysics and religion. There the focus is with supernatural realms and disembodied gods. Nothing can be proved or falsified. Great! Doesn't anyone see the absurdity of this?

Don't we realize that the loss of the original participation with nature gives rise to any number of inauthentic compensatory replacements?

We've got them in plenty. This is why, contra Buber, Heidegger was wary of prioritizing the human to human (or I-Thou) dynamic. He put the emphasis on the quality of the individuals involved. What we have in society today is banal "chit-chat," designed to help humans evade their beinghood.

If this were not the case, there'd be no urban gulags or abuse of nature. There'd be no depression, anxiety and hang-ups. There'd be no neuroses, suicides and homicides. Society would be utterly transformed. In the words of Erich Fromm, there'd be biophilic rather than necrophilic cultures.

|

|

In its annual report on the state of mental and physical health of citizens of the United States, the National Institute of Health reported that Major Depressive Disorder is the leading cause disability in the US for ages fifteen to forty-four. It affects approximately 14.8 million American adults, or about 6.7 percent of the US population age eighteen and older in a given year and is more prevalent in women than in men - Albert Linderman

MIT senior lecturer Otto Scharmer reports that three times as many people worldwide take their own lives than people who take others' lives in all the wars and murders combined - ibid |

|

|

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) and Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) were writers and philosophers dedicated to the role of nature. They established the Trancendentalist Movement in America, inspired by German and English Romanticism and Idealism. Their heroes were Walt Whitman, Goethe, Schelling, Wordsworth, Shelley and Coleridge, etc.

|

|

Kierkegaard dismissed human to human engagement for just these reasons. The dialogue of two or more mediocrities doesn't normally lead to anything profound and meaningful. Such encounters do not strengthen one's sense of identity, in fact they weaken it. This is the sphere of Das Man not Dasein.

Heidegger took a similar view. However, unlike Kierkegaard, Heidegger did not turn to God and Jesus as the means to holistic dialogue. He preferred to concentrate on the lineaments of the all too human mystery - experienced in the here and now. His focus was the primordial Self-World communion. It gave rise to philosophy and we need to return to it if disaster is to be averted.

Heidegger took a similar view. However, unlike Kierkegaard, Heidegger did not turn to God and Jesus as the means to holistic dialogue. He preferred to concentrate on the lineaments of the all too human mystery - experienced in the here and now. His focus was the primordial Self-World communion. It gave rise to philosophy and we need to return to it if disaster is to be averted.

|

|

...humanity’s relationship to nature for the past several centuries has been markedly psychopathic without the slightest semblance of Eros - Adolf Guggenbühl-Craig (The Emptied Soul)

|

We are not to turn to nature in a purely recreational sense. We are not to merely think of it as some attractive decoration to our urban incarceration, or as a resource from which to construct our ugly towns and cities.

Our comportment toward nature must be sincere, humble and grateful. It holds in trust, and reveals the essence of our authentic identity, not just in vast sunlit landscapes, but also in the single fallen leaf, petal or raindrop.

Our comportment toward nature must be sincere, humble and grateful. It holds in trust, and reveals the essence of our authentic identity, not just in vast sunlit landscapes, but also in the single fallen leaf, petal or raindrop.

. . .

Michael Tsarion (2022)